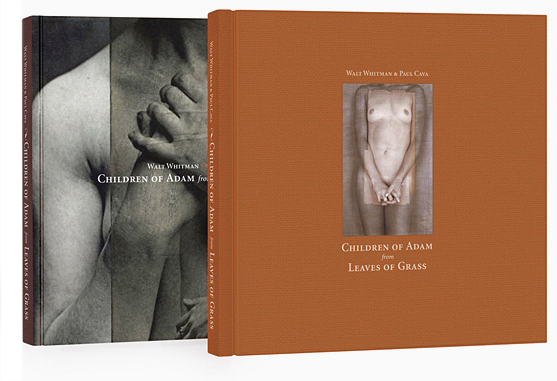

Paul Cava’s Children of Adam: The Arts of Juxtaposition and Delight | by JOHN WOOD

Paul Cava is one of the most radical yet one of most traditional of contemporary photographers. The beauty and sensuality of his work are obvious, but his is an art that can at first appear perplexing When one looks at his photographs of other photographs upon which he has overlaid birds, grids, letters, botanical illustrations, his own paintings, other paintings, one could conceivably wonder, “What does Paul Cava’s work mean? What is Cava saying?”

Photography’s impact on modern art is profound because it freed artists from the tyranny of reality and left them free to pursue impressions, symbols, cubes, and abstractions. And photography, of course, soon found it could do the same thing. But more fundamental than freeing painting from realism, photography freed meaning from the social and historical collection of references it had so long been bound to – primarily those of Classicism, Christianity, and Romanticism.

Artists in distancing themselves from the old fashioned, weighty meanings of the past invented new visual grammars. Consider Mondrian’s work, for example. His geometric abstractions do possess meaning, but meaning having nothing to do with gods, archetypes, the brotherhood of man, or the spirituality of Nature, yet having much to do with juxtaposition and what juxtaposition can suggest.

We understand the grammar of a painting of Ulysses strapped to the mast and lured by the overpoweringly seductive song of the Sirens. Apart from the formal statements it might make, it makes two factual statements: This is Ulysses, the mythic hero, and You, too, can be overpowered by sexual Sirens if you are not careful. Mondrian’s grammar is different; it is invitational. It coaxes us, Look at the juxtaposition of these shapes and asks us, Do these juxtapositions suggest anything to you?

Mondrian’s grammar had far less to do with telling than with showing and suggesting, and so the question of meaning shifted from “What does it mean?” to “How does it mean?” But because traditional meaning is so embedded in our thinking, we sometimes think that it is the only kind of meaning, and so when confronted with strikingly original work such as Cava’s, we are left feeling baffled.

But the grammar of Cava’s work is also the grammar of juxtaposition. By placing birds on the naked breasts of a woman; words about God and Cummings on the bodies of lovers; a rising bird and Nature breaking forth and lifting from the union of two lovers; a North/South grid making reference to the Principal Meridian on the bodies of a wrestling Adam and Eve; Christ’s deposition from the cross perfectly fused with but upside down from another Eve offering the temptation of the bitten fruit; the crucified Christ fused to the body of boy; a surging wave beside a naked man, Cava invites us to consider the images themselves and then the interplay of the powerful, dynamic, and richly meaningful juxtapositions he has structured. What could be less baffling or more potent than what Cava presents us with: the sweet humor of birds aflutter on a girl’s breasts; the tantric notion of the sacredness of sex, how at that moment of orgasm the ego is shattered in divine ecstasy and we feel one, not only with our partner but with the One; the idea of Nature herself rising from the union of lovers; Adam’s wrestling with Eve engendering human life on earth; Christ’s and Eve’s sacrifice conjoined, his relinquishment of life on earth and hers of life in Paradise; the recognition that Christ isevery child; and finally that the power of sex is like the power of surging waves, waves that can dash and destroy us as well as give us delight?

That word delight lies at the heart of Cava’s meanings. Too often we forget that delight is its own rationale and purpose, that it is an expression of the joie de vivre. Cava’s is a joyous art, an art of delighting in life – of finding certain surprising things side by side and the delight of those individual things in themselves. And it is also about the delight of beauty. For all of Cava’s modernity, he has wisely chosen not to make the mistake of many contemporary artists and turn his back on beauty. His paintings and photographs may be untraditional in their approach to meaning, but in terms of their subject matter and their commitment to beauty, his art is richly centered within the tradition. Look at what he gives us: lovers again and again, beautiful bodies, birds, trees, leaves, and a recognition of the presence of the divine. These are the great traditional subjects of art. Cava’s art like Walt Whitman’s is an art of delight, a delight in the frolicking of the children of Adam.

A great deal of human delight, as any honest individual would be quick to admit, is found in sex. Whitman knew this and so does Paul Cava. The sexual honesty and frankness of Cava’s art mirrors Whitman’s, who throughout the Children of Adam expressed emotions like these: “Give me now libidinous joys only” (Native Moments); “Without shame the Man I like knows and avows the deliciousness of his sex / Without shame the woman I like knows and avows hers” (A Woman Waits for Me); and “Lusty, phallic, with potent original loins, perfectly sweet, / I, chanter of Adamic songs, / … [am] Bathing myself, bathing my songs in Sex” (Ages and Ages Returning at Intervals).

As I said, Cava’s work is always beautiful, but his “Untitled (Cummings)” is rapturous, as well. One is struck with the beauty of the lovers’ heads, the woman’s breasts, her hips, thighs, their union, the bed, the pillows, and the script declaring God’s power, wisdom, and presence. Here is sheer delight, the very song of the body electric, the essence of joie de vivre – and something that speaks to the spirit as well, that invokes the name of the most holy in the midst of great passion. Cava, like Whitman, is a master at yoking the sensual to the sacred. “If any thing is sacred the human body is sacred,”Whitman declared in I Sing the Body Electric. In the final section of that poem he enumerates the parts, including the sexual parts, of a man’s and a woman’s body, and then concludes the entire poem with these words: “O I saythese are not the parts and poems of the body only, but of the soul, / O I say these are the soul!”

The sequence of photographs accompanying I Sing the Body Electric is one of the most moving unions of poetry with photography in this book. Cava begins his sequence with Sexual Nature #11 (®III) a meditation upon the age-old connections between eros and thanatos, sex and death, two of Whitman’s principal themes. He juxtaposes a grand odalisque of electrical sexuality with a collection of human skulls. If this were not potent enough, Cava links the two with a sequence of four eggs. One’s head swims with archetypes and poetry: procreation and death; creation and decay; death and the maiden; youth and age; the petit mort of orgasm; the “four light-green eggs spotted with brown” from Whitman’s great poem “Out of the Cradle Endlessly Rocking”;Whitman’s “What indeed is finally beautiful except death and love?” from the Calamus sequence; and much more.

Next Cava in his Man and Woman and his Woman and Man shows us the male and female bodies as Whitman does within the poem, but he also blends male and female sexuality, as does Whitman throughout his work. Then finally in Sexual Nature (Blue #5) Cava appears to come to the same spiritual conclusions Whitman arrives at in his conclusion. He presents us with the same four birds’ eggs, the beautiful body of a pregnant woman, and a nude man – but all cast in rich blue, a significant spiritual color in a variety of faiths, and as negatives.

To Whitman, to William Blake, and to many mystics throughout history, the body and the soul are seen as one, yet there must be some kind of difference or we would not have the distinction, and that difference Cava subtly suggests by use of the negatives. It is still the body and the body’s richness we see, for how can one come to the spirit other than through the flesh; how can one know a thing other than through the senses; and if the thing we seek to know is intangible, how can it be known without making it tangible, without making it physical?

Cava also addresses this physical/spiritual dilemma in one of his richest and most moving works Venus/Ember/Ferris/Christ, a powerful blending of the sensual and the sacred. Between the eroticized woman and the crucified Christ we see a shape from a 1997 painting now transformed into a hot, glowing ember. The ember suggests the Venus of Willendorf but also the Sacred Heart burning at the painting’s dark center, afire there between Christ and Venus herself. Cava’s juxtapositions of god and goddess and deliberate centering of the sacred fire of Christ’s heart and Venus’s passion flood the image with meaning. Christ is not only crucified but broken on the wheel, not the wheel of the Middle Ages but a wheel of the modern age. The supports of the wheel vector directly into the flaming heart-ember, while a delirium of sensuous colors vibrates between Venus and her glowing passion. Cava invites us to delight in how these various elements mean, and we are each affected in different ways because the grammar is not declarative but suggestive and invitational. Cava’s invitation to delight is, of course, the invitation to the sexual, as well – even in a work using religious imagery and making a serious moral and ethical statement about the modern age.

Certain foolish, prudish types are sure that artists are always using sex in their work deliberately to shock and scandalize them. They don’t realize the sexual also contains the spiritual, that it contains the world, and that, like delight, it is its own justification. “I hear and behold God in every object,” chanted Whitman in Song of Myself.

SEX CONTAINS ALL, BODIES, SOULS,

Meanings, proofs, purities, delicacies, results, promulgations,

Songs, commands, health, pride, the maternal mystery, the seminal milk,

All hopes, benefactions, bestowals, all the passions, loves, beauties, delights of the earth,

All the governments, judges, gods, follow’d persons of the earth,

These are contain’d in sex as parts of itself and justifications of itself.

FROM A WOMAN WAITS FOR ME

In the pure art of Paul Cava and Walt Whitman love and sex are joined and the height of eroticism is so pure and chaste that life is only life after love:

Love-thoughts, love-juice, love-odor, love-yielding,

love-climbers, and the climbing sap,

Arms and hands of love, lips of love, phallic thumb of love,

breast of love, bellies press’d and glued together with love,

Earth of chaste love, life that is only life after love,

The body of my love, the body of the woman I love,

the body of the man, the body of the earth.

FROM SPONTANEOUS ME

Paul Cava’s work invites us to a garden of earthly delights but reminds us of its proximity to the garden of heavenly delights. Looking at his work is rather like listening to the music of Charles Ives, another American seer who was just as unusual, brilliant, and original as Walt Whitman and Paul Cava. At first Ives’s music sounds a bit strange, but when we listen we realize we know the tune, and when we listen carefully we often realize we are in the presence of a hymn.

May 2005