Interview with Paul Cava by Heather Snider | Published in Eyemazing Magazine, Issue 03-2009 Courtesy of Susan A. Zadeh, editor and founder

Paul Cava is an artist, collector, art dealer, and publisher based in Pennsylvania. His love of photography manifests differently in each of these facets of his professional life, but there is an aesthetic association unifying his work as an artist with the work he collects and the art he chooses to represent. His own art explores the spiritual essence of the body through a hybrid of photography, painting, and drawing and was featured in Eyemazing Issue 2, 2006. His work incorporates many of the textures and incidental markings found in 19th and early 20th century vintage photographs. This blending of a contemporary voice with historical underpinnings is a distinguishing feature of Cava’s work. It is not surprising that since 1997 he has also been collecting tintype photographs, an early vernacular form of photography that embodies the mysterious and evocative qualities Cava is clearly drawn to. Featured here is a small selection of Cava’s impressive tintype collection.

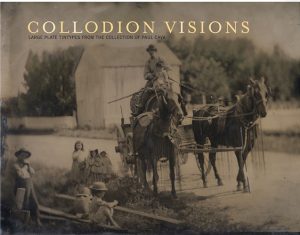

Tintypes had the longest period of popularity of any print type other than silver gelatin prints. The tintype process was invented in the 1850s and tintypes continued to be produced, primarily by itinerant photographers, through the 1930s. They were the least expensive and time intensive of all the early photographic processes and made photography available for the first time to the working classes. Because of this they recorded a wider picture of society than did daguerreotypes or ambrotypes, the other well-known photographic processes of their time. Though tintypes were most often produced as small-scale keepsakes, Cava’s collection of approximately 200 works is composed primarily of large plate tintypes ranging in size from 4 x 5 to 9 x 7 inches. We interviewed Cava about his collection, discussing the tintype medium from both a collector’s perspective and in relation to his own artwork.

Heather Snider: Can you give a brief explanation of the tintype medium especially as it inspired you to begin collecting?

Paul Cava: When I began my relationship with fine art photography in the mid-1970s tintypes were not in my sphere of interest, primarily because they lacked the “look” of the sort of historical fine art photography I was accustomed to. It wasn’t until 20 years later that I began to be seduced by their dark secrets.

HS: Can you speak a bit about the tintype process? Why did you focus on tintypes as opposed to another 19th century form?

PC: Let me first say that I do collect other forms of photography, tintypes being a small but very dear and personal part of my photography collecting interests. The tintype, or ferrotype, is made by coating a thin sheet of lacquered iron with an emulsion of light sensitive collodion and then making an exposure. The resulting image is actually a negative that appears positive and is inverted so that the image is laterally reversed. Although there is a difference in the technical processes between the daguerreotype, ambrotype, and tintype, the major difference in terms of my appreciation of the three mediums is cultural and aesthetic. The tintype was the first truly popular American photographic medium. Being less restrained by the “academic” conventions that the other two upper-class mediums were mired in, the tintype was free to evolve. Not to say that the tintype wasn’t predictable, it was, but it was looser and it’s practitioners had a more relaxed approach. Jean Cocteau, the French poet and filmmaker once said that cinema would never become real art until it was as affordable as a pencil and paper. In some way this is the appeal and potential of the lowly tintype for me.

HS: As a collector, what do you look for in a tintype?

PC: I don’t “seek” anything in particular, I rather discover through what the image reveals and this is often a fortuitous blend of time, process, and the photographer’s ability to work with his subject.

HS: How you would explain the merits of one tintype over another to someone new to collecting tintypes?

PC: There are no hard and fast rules about this. For me, I would say that visual engagement is primary. I have to be interested in looking. Wanting a tintype because it is a civil war soldier with a gun doesn’t do it for me. I’m not interested in the conventional collecting categories such as post-mortems, civil war military, or trade occupationals that many hard case image collectors gravitate towards. Also, large size and surface are important considerations for me. Condition is of some importance but is not a deal breaker. I don’t mind imperfections so long as they add something to the content and expression of the image. A good example of imperfection that works positively is the mother and girl with doll or the Pennsylvania oil wells—both gain gravitas and meaning from their imperfections. Also, the thing to remember is that there is only one example so it isn’t like you can order a better one. If the image moves you, go for it.

HS: Most tintypes are portraits of some form. Do you ever research the subjects, and if so how far do you go, to find out who these people were?

PC: I have no historical interest in these individuals beyond my personal response to the image, object or place that the tintype presents. Although the individuals pictured are all unknown to me, I find it remarkable to discern, a century and a half later, a living and breathing connection through their soulful expressions. I suppose what draws me to them is a sense of recognition, a sense of self: the stern righteousness of the freemason, the delight in the eyes of the girl with the polka dot dress, the poignant isolation in the woman’s face with thin hair, the awkward impatience of the twin boys. All of these expressions speak to me and are of me in some deep way. I find in these humble tintypes, made so long ago, the universal aspect of art that can transcend its original time and place and be so endearing to viewers nearly a century and a half later.

HS: I am taken by the tintype of a woman and girl perched in a tree by a rowboat. Something about this photograph is so odd and also so real. What do you know about this image, where did it come from, what do you think it is about?

PC: I agree with you, it is a super image, rich with symbolism: the bare trees, the elegant woman in the black formal dress, the contrasting girl in white apparently levitating above the boat that is moored in the dark water below. Great art asks questions while it thrills the senses and this one accomplishes both. It is the most recent acquisition in my collection, proof that there are still gems out there waiting to be discovered.

HS: Can you talk about the cracking in the emulsion of Pennsylvania Oil Well and how such aspects affect both the aesthetic and the value of a tintype?

PC: Well, technically the cracking of the collodion on this plate is caused by extreme temperature shifts causing the emulsion to crack, but the “damaged” effect in the Pennsylvania oil field is a prophetic vision of the future with its blood red veins breaking through the sky. To describe it as apocalyptic is an understatement. This is a perfect example of how time and process play a major role in transforming a documentary image into a powerful contemporary metaphor. Our eyes see these images differently from their makers.

HS: Can you elaborate on that last idea, about the differences in how we perceive these works in the present day versus how they were perceived at the time they were created?

PC: There is a whole range of photography that is collected today that was not intended by its makers to be art. For example, I have a collection of photographic figure studies made by the renowned early 20th century painter, muralist, and printmaker Frank Brangwyn. Brangwyn used these photographic figurative studies as guides to transfer his images to canvas or panel. Many of them are squared-up in pencil or ink or in some few cases actually scored with a knife to create a working grid. These prints were technical necessities for the artist’s elaborate allegorical narratives but they come down to us through our 21st century eyes as powerful poetic entities in their own right. A more obvious example of what I mean are the graphic news photographs of Arthur Fellig (Weegee) made in the 1940s and 50s. These raw documentary news photos have an afterlife that transcends their original purpose. It is the same with the work of 1940s Heber Springs studio photographer Mike Disfarmer, or the early 20th century Philadelphia street portrait photographer John Frank Keith who photographed his working class neighbours. Because of the monumental work of August Sander and Lewis Hine our eyes and minds have been attuned and we can appreciate the work of Disfarmer and Keith today. There are thousands of other vernacular images by anonymous photographers that have been transformed by time. Context is everything in art.

HS: How has the market and being a collector of tintypes changed since you started?

PC: Drastically. Large plate tintypes of quality are an endangered species. Gone are the days when such images could be had for a song, however there are still opportunities if one is diligent I suppose. As prices increase I would expect that more would come to the auction market.

HS: Where do you find tintypes?

PC: It is becoming more and more difficult. The obvious places to look for them would be photography dealers, antique shops, photographic fairs, auction houses, eBay, and estate sales.

HS: It seems that you collect more as an artist searching for a kindred vision than for the purpose of putting together a specific collection? Would you agree?

PC: I collect for the joy of recognition and the comfort of knowing that life is a continuum and that certain things of beauty and wonder are worth saving and in some way contribute to an understanding of my self.

HS: Can you give an example of something you may have learned from viewing a tintype, or how something you saw in a tintype made its way into your artistic process?

PC: There isn’t a particular tintype per se that jumps out in this regard. I became more aware of the dark beauty inherent in the tintype’s reduced tonal scale in the 1990s when I was beginning my Ink series. This is a series of photo-lithographic reproductions on paper that I applied black and white ink to either by hand or with various tools. The resulting images share an obvious sensibility with the reduced tonality and markings evident in tintypes. It’s difficult to discern if my interest in collecting tintypes was informed by my artwork at the time or if my artwork was influenced by the tintypes but there is clearly a visceral relationship between the ink series and the tintypes.

HS: Have you encountered other artist collectors such as yourself?

PC: Many artists collect things that inform their work either directly or indirectly. I think for an artist to collect work that is not in some way relative to what he or she is thinking about would be a distraction.

HS: Are there other significant tintype collections that you know of or admire?

PC: Well, there have been a few books on the subject published but nothing that I would call distinctive in terms of a particular collector’s vision. They are mostly generalist overviews of the medium. The recently published America and the Tintype by Steven Kasher (Steidl/ICP; 2008) is the best that I am aware of. It’s a difficult area to navigate because so much of tintype production was just that, portrait production for the masses. Without the star practitioners of its more respected cousins, the daguerreotype and ambrotype, the tintype was left to its own devices. Ignored by photography historians until very recently, the history is just being written which is why it is an exciting time to be collecting tintypes. I know there are certain individuals building collections but they are being quiet about it. I would expect that the market would determine when these more refined collections begin to surface as the scarcity of great tintypes becomes more evident and their value increases.

HS: Are you still collecting?

PC: I am not an aggressive collector in this respect. I don’t seek out tintypes—they find me and I prefer it that way.