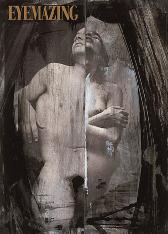

Eyemazing Magazine interview with Paul Cava | by STEPHEN PERLOFF Issue 02-2006

Stephen Perloff: Paul, your new body of work, Children of Adam, is inspired by Walt Whitman’s poems. The quintessential American poet, Whitman has also inspired photographers like Edward Weston and Duane Michals. What was it about Whitman’s work that intrigued you? And is there something about it that lends itself to collaboration with photography?

Paul Cava: The new Children of Adam book and recent exhibition at Gallery 339 in Philadelphia was comprised of photo-based work from the past 25 years and none of it was made with Whitman’s poetry in mind. I love Whitman for many reasons, primarily his inclusive ease and naked honesty regarding the body and it’s relationship to the soul or spirit. I always felt a sympathy between my art and these poems but never thought of formalizing a response until I was asked by the German publisher, Alexander Scholz, if I would care to do a project with him. Alex is a unique and courageous young publisher who had expressed interest in my art and thought he might like to publish it. I pitched him the idea of Children of Adam and he liked it. I don’t know if there is something about Whitman’s poems that works well with photography per se, but I do know that it is uncanny the way the effect of my work and his words lock together.

SP: In these images you have employed photographs you’ve taken of your wife, historic photographs — some well known, some not — and found pornographic imagery, as well as religious imagery of Christ’s body. All are united by their sensuality and your handling gives them an authenticity that is authoritative. This references a long tradition going back at least to Renaissance painting (although here in the United States this could be controversial among religious conservatives). It also celebrates the human body and human sexuality in a way that perfectly meshes with Whitman’s poetry. How and when did you discover this natural connection and what other imagery, literature, or other art forms inform this work?

PC: In regard to the anonymous found images that I sometimes use in my work, I feel that the origin of the source material is irrelevant to the end result and I like to think that I am liberating such images by recontextualizing them. Images of sex are not necessarily pornographic. The core of the beauty in my work is about Eros in a general sense, or love, not sex, and so I am saddened when some people claim they see pornography in my work. I am not a religious person but I believe the story of Christ is the story of love and it’s accompanying suffering and sacrifice. I attended Catholic school when young and the power of this symmetry was not lost on me so Christ makes repeat appearances in my work. Another less religious way to view this relationship of love and loss, creation and destruction, is as Eros and Thanatos, the two timeless halves of being. It’s not a new story in art and literature. These are passionate instincts that artists have grappled with since the cave paintings at Lascaux.

SP: Those who see pornography are too quick to condemn any depiction of sex and deny its relationship to love. I think part of the achievement of your work is in melding those concepts.

Your work here is both synthetic and organic, melding your own imagery and/or appropriated imagery in a very convincing way. You were doing this when I first saw your work some 30 years ago. An early signature print — Run, Puff. Run, Puff, run. — combined a page from a children’s book, Eddie Adams’s iconic image of a South Vietnamese police chief killing a Viet Cong suspect, Harold Edgerton’s sequence of a bullet ripping through metal plates, and images of Niagara Falls and an X-ray of a skeleton. How did you start doing this and how has it evolved over the years? What were the influences and inspirations from seeing photographs and other images over your many years as a photography gallerist and dealer?

PC: I think the question of influence is multi-dimensional. Another way to ask the question is to examine the needs of the individual that require the influence. Photography in the 1970s was a rather inbred, restricted art form and as a young artist interested in the medium I was reacting against this. The straight photograph was not satisfactory for me; it lacked the physical and emotional intimacy I craved, so I began to mess around in unorthodox ways like in the Run, Puff, Run piece from 1976. When I think back to that early work I can see the influence of Robert Rauschenberg — he was important for me in terms of loosening the photographic rectangle and for his mixing other media with photography. Just before the time that piece was made, during my graduate studies at Rochester Institute of Technology in the early/mid ’70s I became immersed in the history of the medium and would spend days at the George Eastman House studying the early non-silver processes by the Photo-Secessionists. One summer in Paris I immersed myself in the photographic work of the French primitives from private collections and at the Bibliothèque Nationale. All this research provided me with a strong foundation to build from and later deconstruct. There were years in the 1980s when I put photography aside and only painted, so my influences are varied and plenty and not simply visual.

SP: How did you meet Alexander Scholz? What other projects has he done? Your book is very elegant, beautifully designed and printed. Is that something for which he’s known?

PC: I met Alexander Scholz through the internet — a modern high-tech match made in heaven. He contacted me because of my photography activities. He grew up in East Germany and is an architect by trade and a publisher by vocation. He has published literary, audio, and visual works by a diverse range of artists such as William Burroughs and William Blake and contemporary artists such as the photographer Thomas Karsten. Alex isn’t afraid of difficult subject matter and is planning a book that pairs 19th-century photographs of skin diseases with the contemporary poetry of John Wood, not your typical art book publisher.

SP: Your reference to Robert Rauschenberg is apt. Warhol also melded photography and printmaking, but both of them were classified as “artists” rather than photographers. It was only recently with the reinstallation of the galleries at the Museum of Modern Art that Rauschenberg and Warhol were included in photography. Your technique has often been similar but you’ve tended to classify it as photography. (Or have others done that for you?) How do you see the placement of your work and how is that affected and how is it changing with new digital technologies?

PC: My work has been compared to Warhol before, in fact my publisher has made the comparison, but I must say I don’t see it. Perhaps, we both trespass on photography’s respectability in our appropriation and unorthodox use of images but the effect and intent is quite different in my work. My work tends to embody an intimate, emotional situation whereas in Warhol’s work the image is iconic and impersonal, a promotional sensibility — really quite the opposite of what I am after. Scale is an issue as to how photo-based work is perceived. If I were to work large like Rauschenberg the connection would be more easily aligned with painting. As photo-based work keeps infiltrating the museums these category distinctions will hopefully dissolve. Defining artists with the medium they happen to be working in just keeps artists and art restricted. Artists who work in various or crossover mediums are plagued by this problem of categorization in applying for fellowships and grants. It’s an obsolete format and the institutions that keep it alive should abandon it. The new digital technologies create an even more ambiguous environment. I think of art in culinary terms, the medium is just an ingredient in the final dish and my favorite cuisine these days is Photo-fusion.

SP: Having your work published marks a kind of completion. Do you feel a need to move on into new territory or is there much more to mine in this vein? Do you have any sense of what’s next for you?

PC: Since doing Children of Adam the opportunity has come up to collaborate on a book project with the Australian poet Alison Croggon. It would be a departure in that I have never made work in response to specific writing before. As I said earlier, my work for Children of Adam all existed prior to its relationship to Whitman’s poems. This would be quite different; I generally let the work direct me. We’ll see how things evolve. I’ve wanted to work more loosely, perhaps pushing the physical and the scale relationships more. I feel the stylistic nature of my work is beyond my control; it’s what feels natural. I can’t imagine consciously changing anything at this point.